Crossing the Panama Canal

Sailing was something I never thought I’d do. I never even thought about it. Then I met Ron. He talked about it with so much passion I was afraid I had been missing out. When I was planning my trip to Australia he was selling all his earthly possessions to purchase a 47-foot sailboat he called, “Yemaya.” When he asked if I’d like to come aboard for a month…well, there was no way I’d say no. A year later, I arrived in Panama. I saw Ron before he saw me. He had already been sailing for a year and looked the part of a ship captain. It was good to see my old friend and we shared whatever gossip from home had trickled down to our part of the world. The taxi dropped us off on the Pacific side of Panama. It was dark as we climbed into a small wooden motorboat. Ron gave directions in broken Spanish to the man steering us in the direction of my new home as we weaved in and out of sailboats—some looked like they’d been anchored for decades. When Yemaya came into view I took a deep breath and held it. Even in the dark she looked impressive. Her masts were down; she was swaying gently in the wind. The Bridge of the America’s, which connects North America to South America, stood proudly in the background.

A year later, I arrived in Panama. I saw Ron before he saw me. He had already been sailing for a year and looked the part of a ship captain. It was good to see my old friend and we shared whatever gossip from home had trickled down to our part of the world. The taxi dropped us off on the Pacific side of Panama. It was dark as we climbed into a small wooden motorboat. Ron gave directions in broken Spanish to the man steering us in the direction of my new home as we weaved in and out of sailboats—some looked like they’d been anchored for decades. When Yemaya came into view I took a deep breath and held it. Even in the dark she looked impressive. Her masts were down; she was swaying gently in the wind. The Bridge of the America’s, which connects North America to South America, stood proudly in the background. Clumsily, I climbed onto the deck. I couldn’t see much and started tripping over ropes, not knowing what I could or couldn’t hold on to. Regaining balance, I followed Ron through the hatch and down the ladder to the gut of the boat. He explained the sleeping arrangements. Ron slept in the bow and Anne (our other crew member) and I slept in the back. My bed was a little cubbyhole about 25 inches wide and 6 feet long. My legs slid back into a little tunnel leaving my upper body exposed. I had a little window, a small fan, and a reading light. My luggage was pushed up on its side to allow access to my bed and the ladder leading to the upper deck. This was to be my personal space for the next thirty days. We didn’t talk much that night because we had to wake up early to pass through the Panama Canal.

Clumsily, I climbed onto the deck. I couldn’t see much and started tripping over ropes, not knowing what I could or couldn’t hold on to. Regaining balance, I followed Ron through the hatch and down the ladder to the gut of the boat. He explained the sleeping arrangements. Ron slept in the bow and Anne (our other crew member) and I slept in the back. My bed was a little cubbyhole about 25 inches wide and 6 feet long. My legs slid back into a little tunnel leaving my upper body exposed. I had a little window, a small fan, and a reading light. My luggage was pushed up on its side to allow access to my bed and the ladder leading to the upper deck. This was to be my personal space for the next thirty days. We didn’t talk much that night because we had to wake up early to pass through the Panama Canal.

By the time I awoke the rest of the crew was on deck. Every vessel that passes through the Canal has to have an appointed pilot and five crewmembers. Our crew consisted of Ron, Greg, Anne, Eric, and myself. Greg had flown in from California for the Panama Canal experience. Eric was a sailor friend of Ron’s. The easiest way to go through the canal is to be tied to a tugboat, but sometimes they are not available in which case the crew would have to hand line the boat through the locks. This is a difficult task, and I had anxiety thinking I’d be the one to drop the line. Fortunately, we were assigned a tugboat.

Roberto was our appointed pilot, an actual tugboat captain. He was a 32-year-old from Panama. He went to University in Brazil to become an engineer of water with the dream of becoming a tugboat captain. He has been all over the world including holding a job on a vessel in the Black Sea. He makes $80,000 a year and has a dog named, J-Lo.  We motored under the Bridge of the America’s and through the causeway to the Pacific entrance into the canal, the Miraflores Locks. We were the smallest vessel in our group. There were two other privately owned yachts and an 800-foot car carrier, which led us into the first lock. We successfully tied up along side our tugboat and the steel doors creaked as they closed behind us. The walls surrounding us were 15 meters thick at the base and 3 meters on the top. As the water rises 27 feet, the turbulence caused the water to swirl in small powerful whirlpools. If someone fell in they’d be taken straight to the bottom. We tied Eric’s dog to the center of the boat. He was getting nervous and we didn’t want to lose him in the whirlpools.

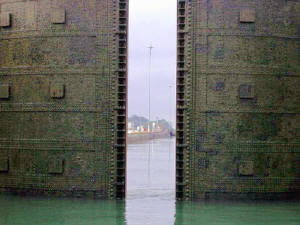

We motored under the Bridge of the America’s and through the causeway to the Pacific entrance into the canal, the Miraflores Locks. We were the smallest vessel in our group. There were two other privately owned yachts and an 800-foot car carrier, which led us into the first lock. We successfully tied up along side our tugboat and the steel doors creaked as they closed behind us. The walls surrounding us were 15 meters thick at the base and 3 meters on the top. As the water rises 27 feet, the turbulence caused the water to swirl in small powerful whirlpools. If someone fell in they’d be taken straight to the bottom. We tied Eric’s dog to the center of the boat. He was getting nervous and we didn’t want to lose him in the whirlpools.

first page here.

<!--pagebreak-->

second page here. Once you rise, you enter a second lock. The cargo ship is connected to mules—special locomotives to pull the ship by cable through the locks. Most ships require three mules on each side. This is quite impressive. The private boats have to switch sides and tie again to the tugboat so a lot of work is involved. The crew threw stern lines from one boat to the next with no time for error. The next lock is San Pedro. It is the smallest lock raising us 10 meters. The tugboat we were tied to, Colon, invited us onboard. This was quite an invitation, to get a tour of something that is such an intricate part of the workings on the canal. Tugboats operate 24 hours a day so it has all the amenities. The Captain allowed us to sit behind the steering wheel and inspect the instruments. Each tugboat costs $8 million dollars and this one had a 5000 horsepower engine. It was a short tour as the locks were filled and emptied in less than ten minutes and each pair of locked gates took only two minutes to open.

Once you rise, you enter a second lock. The cargo ship is connected to mules—special locomotives to pull the ship by cable through the locks. Most ships require three mules on each side. This is quite impressive. The private boats have to switch sides and tie again to the tugboat so a lot of work is involved. The crew threw stern lines from one boat to the next with no time for error. The next lock is San Pedro. It is the smallest lock raising us 10 meters. The tugboat we were tied to, Colon, invited us onboard. This was quite an invitation, to get a tour of something that is such an intricate part of the workings on the canal. Tugboats operate 24 hours a day so it has all the amenities. The Captain allowed us to sit behind the steering wheel and inspect the instruments. Each tugboat costs $8 million dollars and this one had a 5000 horsepower engine. It was a short tour as the locks were filled and emptied in less than ten minutes and each pair of locked gates took only two minutes to open. When the San Pedro doors opened we entered Lake Gatun, the second largest man-made lake in the world, second to Lake Meade (Hoover Dam). Lake Gatun is 32 miles long. It took us five hours to cruise through the lake. It is the main source of drinking water for Panama City and the Gatun Dam is able to generate enough electricity to run all the motors, which operate the canal, including the mules. Water, however, is not pumped into the locks, the locks operate through gravity. As the locks operate, the water simply flows into them from the lakes or flows out to the sea level channel. Of course, this process relies heavily on rainfall to compensate for the 52 million gallons of fresh water consumed during each crossing. The total number of vessels that pass through in both directions is 38 per day. We paid $500 for access but most ships are charged $160,000. The lowest toll ever was 36 cents by Richard Halliburton for swimming the canal in 1928. Roberto was most impressed when a US submarine moved through the Canal.

When the San Pedro doors opened we entered Lake Gatun, the second largest man-made lake in the world, second to Lake Meade (Hoover Dam). Lake Gatun is 32 miles long. It took us five hours to cruise through the lake. It is the main source of drinking water for Panama City and the Gatun Dam is able to generate enough electricity to run all the motors, which operate the canal, including the mules. Water, however, is not pumped into the locks, the locks operate through gravity. As the locks operate, the water simply flows into them from the lakes or flows out to the sea level channel. Of course, this process relies heavily on rainfall to compensate for the 52 million gallons of fresh water consumed during each crossing. The total number of vessels that pass through in both directions is 38 per day. We paid $500 for access but most ships are charged $160,000. The lowest toll ever was 36 cents by Richard Halliburton for swimming the canal in 1928. Roberto was most impressed when a US submarine moved through the Canal. There was no hint of rain the day we crossed. The sun was relentless. I sat near the front of the boat listening to Roberto talk about politics and life on the Canal. There were little islands scattered throughout the Lake and spider monkeys swung from tree to tree. All day I felt like I was part of history. When we arrived at the Gatun Locks we had a bit of a wait and Roberto gave us the okay to jump in. We dove off Yemaya into Lake Gatun. It was such a thrill to cool off in fresh water. The current was strong. A police boat eventually came over and ordered us back onto Yemaya. I guess the strong current and wild crocodiles create dangerous swimming environment.

There was no hint of rain the day we crossed. The sun was relentless. I sat near the front of the boat listening to Roberto talk about politics and life on the Canal. There were little islands scattered throughout the Lake and spider monkeys swung from tree to tree. All day I felt like I was part of history. When we arrived at the Gatun Locks we had a bit of a wait and Roberto gave us the okay to jump in. We dove off Yemaya into Lake Gatun. It was such a thrill to cool off in fresh water. The current was strong. A police boat eventually came over and ordered us back onto Yemaya. I guess the strong current and wild crocodiles create dangerous swimming environment.

The last lock is the Gatun Lock which was to lower us 85 feet back to sea level (down locking). This is where we ran into a bit of trouble. We were in the last lock when the yacht we were paired up with was too slow in tying to the tugboat. The cargo ship was behind us at this point. I never really knew how big those cargo ships were, until we were about ten feet from its hull. The crew looked like soldier figurines from where I was standing. I was chatting with our pilot when we heard the shouting. The crew on the yacht missed our rope toss and we started to spin. The cargo ship went into reverse and its huge propellers created strong prop wash that pushed us faster towards the cement wall. Ron tried to steer the boat but it was no use. Our first reaction was to use our upper body strength to push away from the wall. This did not work and could have potentially broken all of our arms. The wall had layers of thick green and brown algae and our hands slipped right off of it. Ron had tied old tires to the perimeter of the boat. A tire in the front hit the wall hard, which swung Yemaya against the wall sideways. We tossed a rope up to one of the handlers on land and he tied us to a hook. We were secure. One look at the tugboat captain and we knew we were lucky. He said he’d never experienced anything like it and I don’t think he wants to again.

Our first reaction was to use our upper body strength to push away from the wall. This did not work and could have potentially broken all of our arms. The wall had layers of thick green and brown algae and our hands slipped right off of it. Ron had tied old tires to the perimeter of the boat. A tire in the front hit the wall hard, which swung Yemaya against the wall sideways. We tossed a rope up to one of the handlers on land and he tied us to a hook. We were secure. One look at the tugboat captain and we knew we were lucky. He said he’d never experienced anything like it and I don’t think he wants to again. We celebrated our luck by opening a bottle of the best wine on board as we waited for the massive doors of the lock to open and let us out into the Caribbean Sea. The steel doors of the Panama Canal opened as if we were about to sail into a storybook. We had completed what most people, even sailors, never experience. I turned to look at the Canal one last time. The concrete walls and steel locks were truly impressive. It is the greatest engineering marvel of the modern world. A boat motored up beside us and Roberto jumped onto it waving goodbye. He would pass through the Canal once more before calling it a day. As for us, we were to spend a night in Colon before heading out to sea.

We celebrated our luck by opening a bottle of the best wine on board as we waited for the massive doors of the lock to open and let us out into the Caribbean Sea. The steel doors of the Panama Canal opened as if we were about to sail into a storybook. We had completed what most people, even sailors, never experience. I turned to look at the Canal one last time. The concrete walls and steel locks were truly impressive. It is the greatest engineering marvel of the modern world. A boat motored up beside us and Roberto jumped onto it waving goodbye. He would pass through the Canal once more before calling it a day. As for us, we were to spend a night in Colon before heading out to sea.