Dalton Highway

Most rental car agencies in Alaska put a special clause into their rental agreement, with the intention of protecting their vehicles from costly damage.

It reads something like this: "Don't drive on the Dalton Highway, you idiot."

Okay, the term "idiot" doesn't actually appear on any of these clauses, as far as I know. But trying to rent a car to drive the Dalton Highway is almost as difficult as renting one to raft down the Yukon. Rental car agencies just don't allow it. And why should they? Any dirt road can damage a shiny new rental Daewoo, but at five hundred miles in length, the Dalton is special. Tires go flat with the regularity of freshly opened

bottles of soda. Flying gravel quickly turns windshields into cratered surfaces resembling the moon. Frost heaves pound unfortunate drivers senseless.

bottles of soda. Flying gravel quickly turns windshields into cratered surfaces resembling the moon. Frost heaves pound unfortunate drivers senseless.

All the guidebooks are basically in agreement on two points. Point number one is: Don't drive the Dalton yourself; fly to Prudhoe Bay or take a shuttle bus. Point number two is: If you are actually stupid enough to drive the Dalton, be prepared for every variety of road disaster imaginable. Since the nearest service station is hundreds of miles away, for example, towing bills quickly reach four figure sums.

Considering all of this information, there was no question what I was going to do. I was going to drive the damn road all by myself.

Considering all of this information, there was no question what I was going to do. I was going to drive the damn road all by myself.

What's so great about the Dalton, anyway? Well, it's the northernmost road in North America. The only road in the United States to cross the Yukon River and the Arctic Circle. The country's only overland access to the Arctic Ocean, and only road that crosses genuine arctic tundra. Have I sold you yet?

After a virtually endless series of phone calls, I finally was able to find a rental car agency in Fairbanks (a national brand, nonetheless) that offered to rent me a vehicle to drive the Dalton. It was a four wheel drive, an SUV actually used for sport  utility. It cost about the same per day as a Ferrari does in a typical rental market. Additional expense was incurred by the fact that I had the audacity to attempt this rental while under twenty five years of age. All damages would be my responsibility. But they would actually rent it to me in full knowledge of the fact that I planned to use it to drive the Dalton.

utility. It cost about the same per day as a Ferrari does in a typical rental market. Additional expense was incurred by the fact that I had the audacity to attempt this rental while under twenty five years of age. All damages would be my responsibility. But they would actually rent it to me in full knowledge of the fact that I planned to use it to drive the Dalton.

I booked my tickets to Alaska the next day.

And so I find myself standing in the deserted Fairbanks Airport Terminal at six thirty in the morning, ready to pick up my Ford Explorer, still smarting from a night of what, for lack of a better word, might be termed "sleep." (Note to self: do not stay in accommodations listed in the Lonely Planet as "budget", particularly in states with a "midnight sun," particularly in a room with a window facing the spot where the sun would, theoretically, set). I talk to the lady behind the counter. We once again discuss my plans to drive the Dalton. She asks for my license. She begins filling out forms.

"Oh. You're under twenty five."

"Yeah." Twenty three, going on twenty four.

"We don't rent four wheel drives to anyone under twenty five."

Further discussion reveals that a) driving a four wheel drive on the Dalton is in fact allowed, and b) renting a car at a tender and innocent age is also allowed, but c) the combination of these two risqué activities is prohibited. I inquire as to how this fact was overlooked when I a) made a reservation to rent a four wheel drive, and b) was asked my age and informed about the underage driver fee. No adequate answer is provided. Instead, it is suggested that I a) rent a two wheel drive to b) drive the first few miles of the Dalton, which are paved.

Lesser men might have exploded with anger, but I try something else. I attempt the male equivalent of batting

my eyelashes. It must have worked. After a few minutes, she hands me the keys, a conspiratorial look

sprawled across her face. Thank you, Jesus.

It's now seven in the morning, and I have about five hundred miles to go. Most guidebooks, after they are finished obsessively warning you not to drive on the Dalton, will tell you that if you are inclined to make a fool of yourself anyway, for God's sake don't try to do it all in one day. It's five hundred miles, yes, but five hundred miles of rough dirt road where any number of things can go wrong. The most important thing is to Take It Slow. To me this sounds like good advice. But, naturally, I don’t listen to it. Something to do with being bored after driving only two hundred some odd miles, I seem to recall.

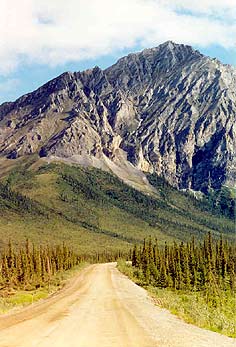

The beginning of the Dalton is unremarkable for anyone who's driven around central Alaska. Forests of spruce, birch and aspen stretch to the horizon in all directions, rolling monotonously over small rocky hills. Groves of regular-sized black spruce are occasionally relieved by groves of stunted black spruce, signaling a bog. The Alaska Pipeline runs right over the landscape, elevated, its snaking path never drifting too far from the road. Occasional turnoffs lead to pumping stations.

The beginning of the Dalton is unremarkable for anyone who's driven around central Alaska. Forests of spruce, birch and aspen stretch to the horizon in all directions, rolling monotonously over small rocky hills. Groves of regular-sized black spruce are occasionally relieved by groves of stunted black spruce, signaling a bog. The Alaska Pipeline runs right over the landscape, elevated, its snaking path never drifting too far from the road. Occasional turnoffs lead to pumping stations.

The first real event of the day is the Yukon River. It's a wide, swift river, flowing through a shallow

spruce-lined canyon. The Dalton crosses it on a half-mile-long rickety, one-lane wooden bridge. That's right, wooden. That’s right, one half mile long. Before you cross the bridge, you look damn carefully to make sure no giant trucks are approaching, and then you are free to cross without significant risk of feeding the salmon.

The trucks, by the way, deserve special mention. The Dalton is also referred to as the Haul Road because it is used to haul supplies up to Prudhoe Bay. The “Haulers”, supply-laden behemoth trucks, had the run of this road until it was opened to the public in 1995, and according to the guidebooks, they still feel a sense of entitlement that prevents them from sharing the road graciously. Thus, mere civilians are advised to pull as far off the side of the road as possible to let the giant trucks rumble by. I can't confirm whether the truck drivers really are unprepared to yield half the road or not, because the moment I saw the oncoming cloud of dust generated by what is known in the Australian Outback as a "road train," I got the hell out of the way.

Further up the road (but still firmly in the realm of the Taiga spruce forest) is the Arctic Circle. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has created a nice little pull-off, where you can pull off and look at a sign saying that you are indeed crossing the Arctic Circle. It's all very exciting. There’s room for at least twenty husky four-wheel drives in the parking lot, but I’m the only one there for the duration of my visit.

Further up the road (but still firmly in the realm of the Taiga spruce forest) is the Arctic Circle. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has created a nice little pull-off, where you can pull off and look at a sign saying that you are indeed crossing the Arctic Circle. It's all very exciting. There’s room for at least twenty husky four-wheel drives in the parking lot, but I’m the only one there for the duration of my visit.

Another BLM attraction is the interactive tundra walk. You can walk through the tundra, look at display boards, and view the Alaska pipeline. Mind you, this is south of the Brooks Range, before you actually cross the treeline. This isn’t true arctic tundra; it’s a kind of high altitude tundra that grows when it’s too cold to for those stunted little black spruces. The walk is popular among the day-trippers, those of weak constitution and minimal ambition who set out from Fairbanks and only manage to get as far as the Arctic Circle before turning around. There are tour buses that perform this very journey,  I’m told, and stop at the tundra walk so the suckers can experience “tundra.” This is a bit like a mountaineering expedition up Mount Sunflower, the highest point in Kansas. It may seem impressive until you cross the Colorado border. They don’t have tundra walks north of the Brooks Range. You just stop the car and get out. Yes, I’m a tundra snob.

I’m told, and stop at the tundra walk so the suckers can experience “tundra.” This is a bit like a mountaineering expedition up Mount Sunflower, the highest point in Kansas. It may seem impressive until you cross the Colorado border. They don’t have tundra walks north of the Brooks Range. You just stop the car and get out. Yes, I’m a tundra snob.

And then, the inevitable midpoint of any journey up the Dalton: the “town” of Coldfoot. You get gas at Coldfoot. You don’t have any choice. The next service station is more than two hundred miles away. It’s also extremely prudent to eat at the log restaurant. For such an empty road, Coldfoot is surprisingly bustling, packed with giant eighteen wheelers, modest SUVs and pickup trucks, even a few hardy sedans. For some reason, images of the spaceport of Mos Eisley come to mind. I wonder whether I should be packing heat.

And then, out of Coldfoot and straight north, over the Brooks Range. Ah, the Brooks Range. There are plenty of remote, rocky mountains in Alaska, and the Brooks isn’t particularly high or impressive in terms of snow cover and glaciers. But the Brooks is a scenic wonder all its own. I approach the south slope first, and what I notice is the rawness of the exposed rock. Granted, most mountain ranges have plenty of raw, exposed rock, but the Brooks Range has the most spectacular I’ve ever seen. It’s as if a giant haphazardly splattered a bucket of molten rock over a boring plain of spruce trees. Great fists and crags of rock push up from the spruce basin at unimaginable angles, vying for your attention. You can see layers of geological time scrawled out across the rocky cliffs, leering at you for not knowing a damn thing about geology. It’s really quite scenic.

And then, out of Coldfoot and straight north, over the Brooks Range. Ah, the Brooks Range. There are plenty of remote, rocky mountains in Alaska, and the Brooks isn’t particularly high or impressive in terms of snow cover and glaciers. But the Brooks is a scenic wonder all its own. I approach the south slope first, and what I notice is the rawness of the exposed rock. Granted, most mountain ranges have plenty of raw, exposed rock, but the Brooks Range has the most spectacular I’ve ever seen. It’s as if a giant haphazardly splattered a bucket of molten rock over a boring plain of spruce trees. Great fists and crags of rock push up from the spruce basin at unimaginable angles, vying for your attention. You can see layers of geological time scrawled out across the rocky cliffs, leering at you for not knowing a damn thing about geology. It’s really quite scenic.

And then, suddenly, everything changes.

The books and maps describe a poignant landmark, the “Last Spruce Tree,” a kind of arboreal outpost before

the endless onslaught of tundra. Somehow, I miss it. Instead, as I climb high into the Brooks Range, I notice that there aren’t any trees. For me, this isn’t particularly remarkable; half the passes back home in Colorado cross timberline. But the difference is that once you start down the other side, there still aren’t any trees. Not one. The angular yellow-green mountains, concealing lingering patches of snow, soon overwhelm anything I’ve ever seen in the lower forty eight. The arctic light, perpetually golden from a low sunset-like angle, dances over the pale green willows and grass. Grassy slopes are darkened by cloud shadows, and then relit by cool sunlight. Rocky streams streak down spongy mountain slopes into gravely valleys. It’s as if I’ve been transported into the ice age. It looks like the cover to a cheap paperback sequel to The Clan of the Cave Bear. I almost expect woolly mammoths to come lumbering out of the next valley.

After reaching the base of the Brooks Range, the arctic coastal plain begins. 150 or so miles of flat arctic tundra, stretching all the way to the Arctic Ocean. The Alaska Pipeline is still right there, snaking alongside the road, elevated on risers. Since there are no longer any trees, there’s no avoiding it. You see it stretch along the road for miles on end. The plain is pockmarked with small ponds and marshes floating on top of the permafrost that lingers right underneath the spongy tundra. It’s actually not completely flat; little mesas and

After reaching the base of the Brooks Range, the arctic coastal plain begins. 150 or so miles of flat arctic tundra, stretching all the way to the Arctic Ocean. The Alaska Pipeline is still right there, snaking alongside the road, elevated on risers. Since there are no longer any trees, there’s no avoiding it. You see it stretch along the road for miles on end. The plain is pockmarked with small ponds and marshes floating on top of the permafrost that lingers right underneath the spongy tundra. It’s actually not completely flat; little mesas and rolling hills keep things interesting. Birds of incredible variety fly through the air, resting on the telephone poles paralleling the road. Was that a snowy owl or a gyrfalcon? (Note to self: bring bird book next time). Oh, and there are some nice wildflowers, too.

rolling hills keep things interesting. Birds of incredible variety fly through the air, resting on the telephone poles paralleling the road. Was that a snowy owl or a gyrfalcon? (Note to self: bring bird book next time). Oh, and there are some nice wildflowers, too.

At the beginning of the coastal plain, I stop to take a picture of the Brooks Range, which is still visible behind me. In my humble opinion, this is the most scenic part of the whole drive. I pull over, in preparation for the unlikely event that another car might come down the road while I’m stopped. I grab my camera. I get out of the car.

Big mistake.

I am quickly assaulted by squadrons of mosquitoes unleashing an attack that makes the bombardment of Iraq look like a barnstorming run.

I have come prepared for mosquitoes. Alaska is known for its killer mosquitoes. After stopping for a potty break in a spruce grove a couple hundred miles back (there aren’t any Exxon Superstations on the Dalton, OK?) and being assaulted by a potent flock of the Alaska State Bird, I applied my extra strength “Jungle Juice” bug repellent quite copiously, ignoring any future cancer risk. And thus, while I encountered plenty of mosquitoes during the first half of my drive, they knew better than to mess with me.

That was before I got to the North Slope.

That was before I got to the North Slope.

I rush back into the car. An entire wing of mosquitoes follows me in. I engage in air to air combat, and make ace almost instantly. My dashboard begins to resemble Sussex during the Battle of Britain. Ha, ha. Eat that, mosquitoes.

Then, I look outside.

A black cloud darkens the area around my window. I’m not kidding. You haven’t seen mosquitoes until you’ve been to the North Slope. Everything else is merely a trial run for the whining death that awaits you in the shallow ponds and streams of the coastal plain. I didn’t voluntarily get out of my car after that. I tried taking pictures with my windows down, but they started spilling in the second I opened my window. Subsequent experiments revealed that all I had to do was stop the vehicle, and a thick swarm of mosquitoes would form outside my window. I recall a statistic learned at Denali: a caribou loses an average of a quart of blood to mosquitoes every day. I do see one lone caribou that day on the Dalton, walking innocently across the tundra. I don’t envy him the hell he is in.

About halfway across the coastal plain, I come across an overturned pickup truck on the side of the road. No stopped cars. No police. Just a big red pickup lying upside down. I stop the car and get out, trying to ignore the whining in my ears. I walk towards the cabin, afraid I’m going to find a Driver’s Ed special. But it’s empty. Whoever was driving got out of here one way or the other. I shrug my shoulders, get back in the Explorer, and drive on. Strangely enough, I will pass the overturned truck on the return trip, still untouched.

About halfway across the coastal plain, I come across an overturned pickup truck on the side of the road. No stopped cars. No police. Just a big red pickup lying upside down. I stop the car and get out, trying to ignore the whining in my ears. I walk towards the cabin, afraid I’m going to find a Driver’s Ed special. But it’s empty. Whoever was driving got out of here one way or the other. I shrug my shoulders, get back in the Explorer, and drive on. Strangely enough, I will pass the overturned truck on the return trip, still untouched.

And then, finally, I see the lights of Prudhoe Bay, shimmering in the distance. It’s not dark, even though it’s ten at night, but they leave the lights on all the time. The town is an amalgamation of Quonset huts and oil well pipes, all on gravel pads. Lights shine from every building and pipe. Guidebooks describe the oilfields of Prudhoe Bay as an ugly scar on the pristine wilderness, but at ten at night, after driving for fifteen hours, two hundred miles from the nearest human habitation, it’s beautiful. It’s like arriving at a Martian colony after a long journey through outer space. And the town really is more like a space colony or Antarctic research station than a town. There are no storefronts, no houses. It’s all industrial architecture, a company town forced by extreme climate into pure function. Louis Sullivan would have been most impressed. Few people live here permanently. If one were to make a What’s Hot and What’s Not list for Prudhoe Bay, here’s what it would look like:

| HOT | NOT | |||

| Dormitories | Apartments; Houses | |||

| Supply Depots | Stores | |||

| Cafeterias | Restaurants | |||

| Crude Oil | Gasoline | |||

| Pipes, lots of pipes | All other means of conveying liquid | |||

| Hidden stashes of Vodka | Bars | |||

the most expensive room I will pay for during my entire Alaska vacation. There are officially three hotels in town, but at any moment one or two might be closed to visitors. The lady behind the counter informs me that dinner was over an hour ago, and there are no other restaurants in town. Good thing I have a loaf of stale white bread and some emergency peanut butter and jelly in the car. I throw together a couple of sandwiches, then lay down for a much needed night’s sleep.

the most expensive room I will pay for during my entire Alaska vacation. There are officially three hotels in town, but at any moment one or two might be closed to visitors. The lady behind the counter informs me that dinner was over an hour ago, and there are no other restaurants in town. Good thing I have a loaf of stale white bread and some emergency peanut butter and jelly in the car. I throw together a couple of sandwiches, then lay down for a much needed night’s sleep. I happen to wake up at around three in the morning. I confirm that, indeed, it’s still light out. Then I go back to sleep.

The next morning, it’s time for the oilfield tour. You can’t actually drive the last few miles of the Dalton, into the heavily developed oilfields and Arctic Ocean shore. Instead, you get to ride in a Dodge Ram full of other tourists, driven by an amusing young petroleum engineering student. As we head into the wonderland of pipes, gravel pads, and Quonset huts that is Prudhoe Bay, we come across the last thing I’m expecting to see: wildlife. In this case, two full grown grizzly bears, lumbering through town. I spent my entire bus ride in Denali straining to see little tan specs on the distant hillside that the ranger assured me were grizzly bears. Now, in the middle of a phalanx of pipes, I see a grizzly bears only twenty yards from the van. All my best photographs of Alaskan wildlife have oil rigs in the background.

The next morning, it’s time for the oilfield tour. You can’t actually drive the last few miles of the Dalton, into the heavily developed oilfields and Arctic Ocean shore. Instead, you get to ride in a Dodge Ram full of other tourists, driven by an amusing young petroleum engineering student. As we head into the wonderland of pipes, gravel pads, and Quonset huts that is Prudhoe Bay, we come across the last thing I’m expecting to see: wildlife. In this case, two full grown grizzly bears, lumbering through town. I spent my entire bus ride in Denali straining to see little tan specs on the distant hillside that the ranger assured me were grizzly bears. Now, in the middle of a phalanx of pipes, I see a grizzly bears only twenty yards from the van. All my best photographs of Alaskan wildlife have oil rigs in the background.

It’s almost as if the oil companies have scripted this appearance. Prudhoe Bay—and the indeed the entire northern half of the Dalton—straddles the western border of the perennially controversial Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. In Prudhoe Bay, there are no opponents to drilling in the wildlife refuge. Just in case you had any doubts about the official oil company position, there’s an orientation video that makes it abundantly clear. Their argument is that drilling—in particular, the recently developed special nature-friendly method of tearing open the earth—is about as wildlife friendly an activity as exists. In favor of this argument, I spotted two very bold grizzly bears and several caribou, all strolling through the middle of densely developed oilfields. However, it should be noted that several of the caribou looked decidedly unhappy.

The tour takes you all around Prudhoe Bay, introducing you to every piece of oil drilling detritus imaginable. You see Mile 0 of the Alaska pipeline, where it ceremoniously turns downward and vanishes underground. You see oil worker dormitories. Most of these fellows work long hours for several weeks straight and then get several weeks off, flying far away to a more hospitable climate. Some live as far away as Montana.

And then, the end of the earth. The Arctic Ocean. It looks much like you’d expect—a big gray expanse of water. What’s interesting is that one of the beaches is completely covered with large driftwood trees. Apparently, they flow down the Mackenzie River in Canada, and are then pulled by the current to this very spot. Our guide claims that the natives thought these trees grew under the sea, since there are no trees like this for hundreds of miles.

And then, the end of the earth. The Arctic Ocean. It looks much like you’d expect—a big gray expanse of water. What’s interesting is that one of the beaches is completely covered with large driftwood trees. Apparently, they flow down the Mackenzie River in Canada, and are then pulled by the current to this very spot. Our guide claims that the natives thought these trees grew under the sea, since there are no trees like this for hundreds of miles.

The van stops and we get out for a little stroll on the arctic beach. A couple of people are crazy enough to go for a dip, but being the sensible person that I am, I opt only to dip my hand in the icy arctic water. Yes, it is indeed cold. Then I squint into the horizon. The ocean doesn’t vanish into the haze like I’m used to. Instead, I see a vague bluish curtain, far in the distance. It’s the ocean ice pack. Right now, there are only five or ten miles of ocean between the arctic ice pack and us. Even with global warming, in the middle of July. I have truly come to the end of the earth.

I’ve done it. I drove the Dalton, and it was one hell of a ride.