Ethiopian Outback

The sign in front of the African village’s barber shop actually read “abandon hope all ye who enter”. It is one of those strange anomalous fragments of Western culture that sometimes appears in third world countries, like an abandoned New York City taxi cab, a GAP tee-shirt, or a book of matches from the Ritz-Carlton, completely out of context and completely unaccounted for. It could well be a legacy of the missionary establishment or merely a piece of verse copied from a scrap of paper by a sign painter without a word of English. Whatever the case, I might have been well advised to think twice before choosing this particular barber.

African hair is simply not like the hair of the white man. It is strong and stiff and tightly curled. It does not easily get wet nor can it be easily shaped into any form other than its own. As such, the role of an African Barber is considerably different from that of a European or American barber. He has not so much to cut as sculpt the hair. When this principle was applied to my own comparatively fine and flat hair the results were predictably disastrous. No two adjacent hairs were of equal length and, most curiously, part of my forehead had been shaved in an attempt to give me the McHairstyle no. 5 special. This is what I would take back with me to New York.

African hair is simply not like the hair of the white man. It is strong and stiff and tightly curled. It does not easily get wet nor can it be easily shaped into any form other than its own. As such, the role of an African Barber is considerably different from that of a European or American barber. He has not so much to cut as sculpt the hair. When this principle was applied to my own comparatively fine and flat hair the results were predictably disastrous. No two adjacent hairs were of equal length and, most curiously, part of my forehead had been shaved in an attempt to give me the McHairstyle no. 5 special. This is what I would take back with me to New York.

Thus ended my two-week expedition to the Lower Omo Valley. The Lower Omo Valley is one of the most remote and exotic locations on earth. Set in the outback of Ethiopia, one of Africa’s poorest countries, the Lower Omo can be reached only by driving several days through the roadless bush. Temperatures regularly cap 100 degrees and malaria is endemic. However, this region is home to one of the largest concentrations of mostly untouched tribal cultures left in the world.

When word got out in Addis Ababa that I was planning an expedition to the Omo, the street touts descended upon me like vultures to a kill. As it is so difficult to reach, visiting the Omo Valley is just about the most expensive thing you can do in Ethiopia. You need to rent a heavy duty four wheel drive vehicle, a guard, a driver who knows the ways and who speaks at least a few tribal languages (and believe me, these guys are few and far between and know well their value), and purchase all of your foods and other provisions in advance. Given a potential profit of several hundred dollars in commission from the car rental agencies, the greedy gaggle of touts nearly instigated a full-fledged free-for-all street fight as they jostled to be the first to hand me the business card of the car rental agency of the highest commission. Of course, they were all proffering the same card – it was merely a matter of which one I would accept. In Ethiopia, once you accept a card from one person, then that individual essentially owns you. As a matter of professional courtesy to other touts, no other guide will take you and no other agency will rent to you. Knowing something like this might have been the case, I refused to accept any of the cards – infuriating the lot of them.

know well their value), and purchase all of your foods and other provisions in advance. Given a potential profit of several hundred dollars in commission from the car rental agencies, the greedy gaggle of touts nearly instigated a full-fledged free-for-all street fight as they jostled to be the first to hand me the business card of the car rental agency of the highest commission. Of course, they were all proffering the same card – it was merely a matter of which one I would accept. In Ethiopia, once you accept a card from one person, then that individual essentially owns you. As a matter of professional courtesy to other touts, no other guide will take you and no other agency will rent to you. Knowing something like this might have been the case, I refused to accept any of the cards – infuriating the lot of them.

In the end, I was saved from all of this by the intervention of a Danish friend who lived in Ethiopia and offered to rent me his Land Cruiser for the duration of my expedition. The street touts became so angry at this that they gathered in front of the car in order to prevent me from leaving my hotel compound. In frustration, I was finally forced to call in the police. They asked that I identify the offenders; I did so, and they simply said, “We’ll take care of it.” The next day while driving out of town I saw one of the touts covered in bruises with two black eyes and a nasty forehead cut. It was a harsh lesson in third world police justice, but I could not help the feeling that they deserved it.

It took three days of driving to get to the South Omo region. The first tribe we encountered was the Konso. The Konso are not in fact an Omo tribe, but rather an interesting group that can be met along the way. As they lie just off the main Kenya-Ethiopia thoroughfare, the Konso are used to tourists and work relentlessly on extracting every possible birr from every hapless passer-by. However, their villages are well worth the visit if only to admire the beautiful two story stone huts and elaborate agricultural terracing.

It took three days of driving to get to the South Omo region. The first tribe we encountered was the Konso. The Konso are not in fact an Omo tribe, but rather an interesting group that can be met along the way. As they lie just off the main Kenya-Ethiopia thoroughfare, the Konso are used to tourists and work relentlessly on extracting every possible birr from every hapless passer-by. However, their villages are well worth the visit if only to admire the beautiful two story stone huts and elaborate agricultural terracing.

The Konso village that we visited is, ironically, called “New York”. Nearby a massive valley has been etched out of the soft sandstone in Grand Canyon fashion. The water sculpted stone bears what the locals consider to be a remarkable resemblance to the New York City skyline - hence the name. I have serious doubt that anyone who has actually seen New York City would make such a comparison.

In any case, Konso New York can be best described as a seething cauldron of greed. They demanded an exorbitant entrance fee then additional money for every photo. This, I found, has become the norm throughout the Omo Valley, as the occasional traveler that passes through is the only source of money for the largely pre-economic tribes. In response to this I adopted a camera technique whereby I just sort of pointed the camera in the correct direction and took as many photos as possible - a few turned out surprisingly good, but most needed a little bit of Photoshop work (cropping and level adjustment) to perfect.

The Konso are in a transitional phase regarding clothing. Some missionaries must have come through and handed out a truckload of red and blue striped sport shirts as nearly every Konso has one. However, they have not yet fully mastered the art of wearing western clothing and so women will often stick their head through the head hole or often a ripped arm hole, and wear it as a necklace or scarf, thus leaving the remainder of their upper body unclothed. As for the lower body, the Konso women do have a traditional kind of billowing skirt, made from locally woven fabrics, that is designed to emphasize the size of a woman’s behind. Men wear wrap skirts or nothing at all. Some few have more elaborate Western clothing but wear them in a haphazard fashion. I saw one fellow with a pair of pants that were so tight he could not pull up the zipper, thus leaving the full of his manhood humorously and obscenely exposed. The Konso are one of the few tribes in Ethiopia that have adopted western medical practices. Once a week a wandering government doctor will appear about 20kms from Konso New York and see all patients. On this day people from the villages put their sick on homemade stretchers and carry them the entire way. As it is a difficult journey in sweltering heat – especially for the sick people on stretchers – sometimes people die on the way. When this happens, the locals simply drop the bodies in the middle of the road and leave them for the truck that drives through every other day to carry back to the village for burial.

The Konso are one of the few tribes in Ethiopia that have adopted western medical practices. Once a week a wandering government doctor will appear about 20kms from Konso New York and see all patients. On this day people from the villages put their sick on homemade stretchers and carry them the entire way. As it is a difficult journey in sweltering heat – especially for the sick people on stretchers – sometimes people die on the way. When this happens, the locals simply drop the bodies in the middle of the road and leave them for the truck that drives through every other day to carry back to the village for burial.

It was one such body that we found lying in the middle of the road around a blind curve. We were not going fast, but even at 20kms per hour it was impossible to stop quickly enough, and when we slammed on the breaks, our front wheels skidded on the body. I thought for a moment that we were going to be in serious trouble as it never occurred to me that the guy might be dead! The smart English speaking boy that we hired as a guide got out and literally kicked the body into a ditch on the side of the road and said, “Don’t worry, he dead.” As everyone else watching the event seemed nonchalant, I let the incident pass and we continued on to Turmi.

Turmi is in the heart of the Omo region dominated by the Hamar tribe, an exceptionally picturesque and attractive people who remain true to their tribal customs of dress and lifestyle. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Hamar culture is the Bull-jumping/Woman-beating ritual. This occurs in Hamar villages when, each year, the young men and women of a village come of age. In order to pass the ritual of manhood a boy of 12 or so must jump over as many as 9 or 10 bulls at once. This takes the form of leaping from the ground onto the first bull’s back then jumping from back to back until all of the assembled bulls have been leapt. Exceptionally manly boys will often go back and perform this feat two or three times. Afterwards, a boy is welcomed into the world of men and begins his warrior phase in which he will be allowed one sexual relationship prior to marriage.

Turmi is in the heart of the Omo region dominated by the Hamar tribe, an exceptionally picturesque and attractive people who remain true to their tribal customs of dress and lifestyle. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Hamar culture is the Bull-jumping/Woman-beating ritual. This occurs in Hamar villages when, each year, the young men and women of a village come of age. In order to pass the ritual of manhood a boy of 12 or so must jump over as many as 9 or 10 bulls at once. This takes the form of leaping from the ground onto the first bull’s back then jumping from back to back until all of the assembled bulls have been leapt. Exceptionally manly boys will often go back and perform this feat two or three times. Afterwards, a boy is welcomed into the world of men and begins his warrior phase in which he will be allowed one sexual relationship prior to marriage.

The next stage of the ritual involves woman-beating. All Hamar women over 13 years old have severe scarring all over their backs. When I say severe, I mean that the scars will often rise as much as half of inch off the body and cover the entire back from neck to lumbar. Hamar women court this beating as an attempt to marry well and show that they are strong. They approach the men, who wait with sticks, and tease them outrageously, often hitting them and insulting their manhood, until finally the men get angry and begin the beating. The beating is severe and some of the women appear to have been beaten half to death before their brothers and fathers (the beaters) finally stop. Perhaps there is some signal that the woman can give to stop the beatings, but if so I could not tell. Unfortunately, as the Ethiopian government is cracking down on this tradition, the tribesmen were unwilling to let me carry a camera to the ritual and so the best I can do is show you the scars I was able to surreptitiously photograph.

women court this beating as an attempt to marry well and show that they are strong. They approach the men, who wait with sticks, and tease them outrageously, often hitting them and insulting their manhood, until finally the men get angry and begin the beating. The beating is severe and some of the women appear to have been beaten half to death before their brothers and fathers (the beaters) finally stop. Perhaps there is some signal that the woman can give to stop the beatings, but if so I could not tell. Unfortunately, as the Ethiopian government is cracking down on this tradition, the tribesmen were unwilling to let me carry a camera to the ritual and so the best I can do is show you the scars I was able to surreptitiously photograph.

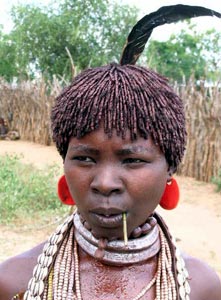

Aside from this severe ritual beating and scarification, the Hamar are a kind and compelling people. I visited several villages and eventually managed to get beyond the one-birr-per-photo stage and befriend a number of Hamar people - no mean feat. One girl in particular, a devilish minx of 11 years, still in the pre-beating phase, followed me around everywhere. Once, when she caught me washing my own clothing she bit my hand in her insistent rage that men should and could not wash clothes. Gender roles are extremely defined in Hamar culture. Men do nothing, women do lots of work, women get beat, men jump bulls, etc. I finally let her do my laundry, and she did a good job for which I paid her six birr.

Hamar women - as well as Karo - cover themselves in a combination of butter and red mud. They do this both to enhance their natural beauty and as sun protection. The substance has a particular odor and, although not totally unpleasant, is strong enough that you know when a Hamar has entered the room, or in most cases, the grass hut.

For the past 10 years, the Hamar have been in a nearly perpetual war with the Galeb tribe. The Galeb traditionally live on the Omo River near Kenya, about 50 kilometers south of Hamar territory. Just before I arrived in the area, a number of terrible battles had taken place in which several people died including a local police officer (Amharan) that attempted to stand in the way of the angry warriors. The Galeb seem to be the primary aggressors, and the biggest issue is cattle theft. Naturally, after visiting the Hamar, it seemed right to visit the Galeb.

For the past 10 years, the Hamar have been in a nearly perpetual war with the Galeb tribe. The Galeb traditionally live on the Omo River near Kenya, about 50 kilometers south of Hamar territory. Just before I arrived in the area, a number of terrible battles had taken place in which several people died including a local police officer (Amharan) that attempted to stand in the way of the angry warriors. The Galeb seem to be the primary aggressors, and the biggest issue is cattle theft. Naturally, after visiting the Hamar, it seemed right to visit the Galeb.

We arrived in Omorate - the Galeb Village - around 10 AM and could not find any of the village men in order to get permission to visit the village. This mystery was solved when we stumbled upon the district police compound where every Galeb male was incarcerated. They had gathered the entire tribe, 150 or so men, into a large courtyard where the local police commissioner lectured them on why they should not kill Hamar.

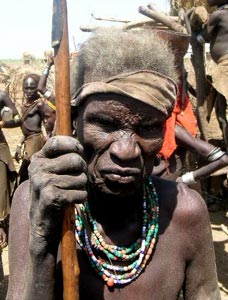

Galeb men, like Hamar and Karo, in a proclamation of warrior might, dress their hair with a kind of clay helmet woven into the hair and decorated with ostrich feathers after they have recently killed someone. Most of these men had their hair shaped into this fantastic design. The police chastising had all of the components of a cult meeting. The commissioner would speak a few sentences, after which the Galeb would reply in unison, ‘ayeea’ (yes). We watched this four about 10 minutes over the shoulder of an angry police officer who finally managed to shoo us away.

Galeb men, like Hamar and Karo, in a proclamation of warrior might, dress their hair with a kind of clay helmet woven into the hair and decorated with ostrich feathers after they have recently killed someone. Most of these men had their hair shaped into this fantastic design. The police chastising had all of the components of a cult meeting. The commissioner would speak a few sentences, after which the Galeb would reply in unison, ‘ayeea’ (yes). We watched this four about 10 minutes over the shoulder of an angry police officer who finally managed to shoo us away.

Since the meeting appeared to have no end in sight, we decided to deal with the women directly. This is a big no-no when there are men around to stop you, but if the women are on their own, they are happy to talk. A spear-toting grandmother who claimed to have mothered half of the Galeb population showed us around. The village itself proved to look like something out of a Star Wars film: low egg shaped grass huts in an empty desert plain.

The generally cheerful and outspoken village women seemed to take a dim view of their husband’s war mongering – freely referring to brothers and husbands as “criminals”. I explained to them that I understood their predicament as my own leader was also a greed-maddened warmonger whose thoughtless violence has caused my village serious problems. To our good fortune, the men never appeared and we were able to finish our visit amicably with the Galeb women.

After leaving the Hamar in Turmi, we drove west along roads that can barely be called roads, to Karo territory. Indeed, they were more akin to openings in the scrub forest that led one to another than anything else. How our driver was able to navigate this is beyond my understanding, as there really seemed to be no discernable landmarks and the distances were too vast to know by rote. Perhaps he just knew which direction to travel in.

After leaving the Hamar in Turmi, we drove west along roads that can barely be called roads, to Karo territory. Indeed, they were more akin to openings in the scrub forest that led one to another than anything else. How our driver was able to navigate this is beyond my understanding, as there really seemed to be no discernable landmarks and the distances were too vast to know by rote. Perhaps he just knew which direction to travel in.

The Karo village of Korcho is set dramatically high on a cliff overlooking the Omo River and a beautiful lake rich in abundant fish and crocodile life. The Karo themselves are closely related to the Hamar but do have some notable differences. First, the Karo have their own unique language. Second, Karo women have a different hairstyle. Whereas the Hamar wear their hair in dreadlocks formed of red clay, the Karo women wear their hair in little beads formed of red clay. Third, the Karo do not perform the woman-beating.

The Karo proved to be forceful business people. As I walked through the attractive Korcho village, I was greeted with aggressive extortions to pay for everything from simple photos to the right to walk past someone’s hut. Faced with such aggression, the visit was a disappointment and ended quickly.

As I was about to leave, one of the village leaders came up to me and asked if we would drive one of their teachers to a village some 200kms away. As it was on our route I had no particular objection but I’d be damned if I were going to do something like this for free when I had just been charged some 125 birr for what was essentially nothing. In a moment of indignant fury, I yelled for some 30 minutes at the astounded chief regarding the rudeness of his village. As my guide nervously translated, the chief frowned more and more. At about this point it began to dawn on me that I was probably going to die. Before me was a six foot five, frowning, naked man with a machine gun and ritual scarification proudly declaring the 50 or so men he had killed during his 40 years as a tribal warrior. When the translator finished the Chief gave his gun to an aide and, to my utter shock threw his arms around me in an embrace. He thanked me for explaining the ways of the white man, apologized for his tribe, and invited me to stay in his home. I accepted and thus began one of the most remarkable experiences of all of my travels.

As I was about to leave, one of the village leaders came up to me and asked if we would drive one of their teachers to a village some 200kms away. As it was on our route I had no particular objection but I’d be damned if I were going to do something like this for free when I had just been charged some 125 birr for what was essentially nothing. In a moment of indignant fury, I yelled for some 30 minutes at the astounded chief regarding the rudeness of his village. As my guide nervously translated, the chief frowned more and more. At about this point it began to dawn on me that I was probably going to die. Before me was a six foot five, frowning, naked man with a machine gun and ritual scarification proudly declaring the 50 or so men he had killed during his 40 years as a tribal warrior. When the translator finished the Chief gave his gun to an aide and, to my utter shock threw his arms around me in an embrace. He thanked me for explaining the ways of the white man, apologized for his tribe, and invited me to stay in his home. I accepted and thus began one of the most remarkable experiences of all of my travels.

Once accepted into the village setting everything changed. Villagers no longer asked for money and instead begged me to photograph them so that they could see their faces in my digital camera. They brought out food and drink and even slaughtered and roasted a goat in my honor. Karo peoples rarely eat meat and the goat-slaughtering gave the entire evening a festive bacchanalian air. Villagers and herdsman gathered from the surrounding countryside to taste the rare meats. Although there is very little food in most villages, they do have a fine local whisky that is most similar to Araki or Ouzo, and packs a similar punch. We got drunk as day wore into evening and the sun set over the village. Our campsite for the evening was not far from the Chief’s hut.

my honor. Karo peoples rarely eat meat and the goat-slaughtering gave the entire evening a festive bacchanalian air. Villagers and herdsman gathered from the surrounding countryside to taste the rare meats. Although there is very little food in most villages, they do have a fine local whisky that is most similar to Araki or Ouzo, and packs a similar punch. We got drunk as day wore into evening and the sun set over the village. Our campsite for the evening was not far from the Chief’s hut.

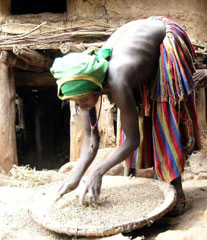

In the morning, we drank a traditional Karo coffee that is brewed rather like a tea and includes the bean husks. This wonderful coffee is mild and delicious and does not require sugar. As I watched the village come to life, I sipped the coffee out of a large wooden bowl carved from the bole of a single massive tree. Women and men emerged from their prospective huts and began the work of the day: weaving and making bean paste (a dietary staple of the entire Omo region), for women, and standing under a shady tree for men. Eventually we said our farewells and the Chief thanked me again for my enlightening words. During the night, he gathered all of the money I had spent on photos and returned it to me and asked me to visit again and stay as long as I liked, for I was now like a man of the Karo.

This beautiful experience was a sharp contrast to my experience with the next tribe on my itinerary, the Mursi. The Mursi are considered the wild men of the Omo Valley. They are the most remote of all Omo tribes, and even among the other Omos they are known for their viciousness. Murder and violence are simply the Mursi way of life: every one of them is a merciless killer and has probably already finished off a childhood friend or two as part of the courtship tradition. They are a purely warrior tribe, and although they have handicrafts, they do not engage in any sort of agriculture. They will however, occasionally lay into an

merciless killer and has probably already finished off a childhood friend or two as part of the courtship tradition. They are a purely warrior tribe, and although they have handicrafts, they do not engage in any sort of agriculture. They will however, occasionally lay into an

elephant with their Kalashnikovs, as they did just before I arrived. The Mursi were only too happy to flaunt the government by proudly displaying the monstrous, fly ridden, steaming carcass. They are also of a different racial stock from the surrounding tribes being of Niliotic rather than Omoiatic / Kushitic origins. The Mursi are known for the distinctive practice among their women of wearing large lip and ear plates. This practice developed to prevent Mursi women from marrying into enemy tribes.

A trip to the Mursi can be best described as visiting a pack of hungry jackals while dressed in raw steaks. The tribe exhibited all of the traits of beasts and none of the traits of humanity. While indeed they are picturesque, they are so unbelievably aggressive as to leave a completely negative impression. Upon getting out of the car, we were immediately grabbed from all directions by the nearly unbreakable holds of the village women while the young children rifled through our pockets searching for money. This makes one very mad, but it is impossible to respond angrily or aggressively for fear it would cause the large, looming, armed, mean and drunk men to attack. I took my photos, they took my money, and I was glad to get out without losing anything else. My entire visit to the Mursi lasted about 30 minutes. And this was the last of the Omo tribes I planned to visit.

Upon getting out of the car, we were immediately grabbed from all directions by the nearly unbreakable holds of the village women while the young children rifled through our pockets searching for money. This makes one very mad, but it is impossible to respond angrily or aggressively for fear it would cause the large, looming, armed, mean and drunk men to attack. I took my photos, they took my money, and I was glad to get out without losing anything else. My entire visit to the Mursi lasted about 30 minutes. And this was the last of the Omo tribes I planned to visit.

On the way back to Addis Ababa, I made my way through the district capital of Jinka and then on to the small city of Arberminch where I visited a stupendously beautiful rift valley lake full of massive crocodiles. These mighty beasts lounged on the beach in groups of 50 or more, each measuring as much as nine meters – yes METERS! – long. Some had heads nearly the size of my entire upper body and could have swallowed a man in a single gulp! Every year 10 or so fishermen are eaten by these crocodiles. At this rate, it will take about 20 years for the crocks to eat all of the town’s 200 fishermen. When I mentioned this to my boat driver, he laughed and said, “Always more fishermen.”

It would perhaps be helpful for new fisherman to read the handy brochure passed out by the Ethiopian Tourist commission entitled, “How not to be eaten by a crocodile”. It contains such useful and practical crocodile avoiding advice as, “If a woman, do not wear a bikini”, “Do not tow large pieces of raw meat, or a carcass, behind your boat”, and my favorite, “If you see crocodiles, do not go swimming.”

Since I did not want to be eaten by a crocodile I planned to follow these rules strictly, but for a moment I did contemplate sticking my head in the water; the croc might have done a better job with my haircut…