Fly Fishing in Burgundy

For many, the mention of Burgundy evokes sensual memories of wine–earthy and complex–and gastronomic adventures among friends.

But sybaritic nostalgia aside, there's another Burgundy that opened herself up to me during a foray into the wooded hills and valleys of the Morvan, a rural land that stretches between Clamecy, Vézelay and Avallon in the north and Charollais and Autun in the south.

Summer in Paris, though popular (perhaps too popular?), is hot, humid and mobbed with tourists. Sure, it’s still Paris and one of the best places in the world to be, even condemned to perpetual gridlock and stickiness, but there are those moments when you catch yourself longing for a cool, tranquil escape. It was one such moment, as I wandered along rue de Grenelle in the seventh arrondissement, that a fly fishing boutique DPSG (Des Poissons si Grands, http://www.dpsg-fr.com, 160 rue de Grenelle, 75007 Paris) rose up from the sweltering sidewalk like a tantalizing mirage.

I entered to find myself in a miniature shop, stocked with the esoteric essentials for fly fishing, “la pêche à la mouche”, and populated by several tweedy late-middle-agers. Despite the intimate quarters, my entrance went undetected. Conversation continued in amicable, chatty French, so I interested myself in the wicker creels and hand-tied flies.

I’d been living in Paris for three years and, aside from a single trout fishing trip to Aveyron in the Midi-Pyrenees, fly fishing opportunities in France had mostly eluded me. I had investigated my options on several occasions and had even joined a Paris-based fly fishing club that permitted me to cast around a private pond in the Bois de Boulogne in pursuit of lethargic catfish and carp. Now, lingering in the boutique transported me to the bucolic streams and rivers of my memory: the bolder-strewn Ausable; the languid Bouquet; the vast, powerful Miramichi; the Dungarven, the Renous,…

I’d been living in Paris for three years and, aside from a single trout fishing trip to Aveyron in the Midi-Pyrenees, fly fishing opportunities in France had mostly eluded me. I had investigated my options on several occasions and had even joined a Paris-based fly fishing club that permitted me to cast around a private pond in the Bois de Boulogne in pursuit of lethargic catfish and carp. Now, lingering in the boutique transported me to the bucolic streams and rivers of my memory: the bolder-strewn Ausable; the languid Bouquet; the vast, powerful Miramichi; the Dungarven, the Renous,…

I was drawn out of my reverie by a smiling character of slight stature and build. A former Sorbonne professor, economist, concert violinist, gourmet and published poet, Michel Winthrop is also a fly fishing guide eager to share his love and wisdom for angling with guys like me. Our conversation was relaxed and easy, somersaulting along in a freeform pidgin accommodating our linguistic needs and limitations. He understood my wistfulness for the rivers of North American, and before long we were arranging an outing at the end of the first week in July to the Parc Naturel Regional du Morvan in Burgundy.

It's eleven o’clock on a Friday night, and we had been in the small car for about four and a half hours. Finally

we had exited the autoroute and were winding along rainy country roads at breakneck speed. Michel Winthrop, piloting our careening compact, had said it would be only another twenty minutes when we left the autoroute. Of course, he’d also assured us that the drive from Paris to Morvan would take scarcely over two hours!

We were three. A colleague sprawled asleep in the back seat, and I rode shotgun, knees against the dashboard, elbow to elbow with Michel who had maintained an uninterrupted stream of conversation since we left Paris. I was ready for the drive to end. Now apparently we were close. I looked forward to arriving. To unfolding me legs. To getting a late supper. To getting to bed.

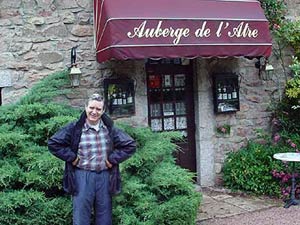

Then we were there, at l'Auberge de l'Atre in les Lavaults (Des Poissons si Grands, http://www.auberge-de-latre.com, Les Lavaults, 89630 Quarré-les-Tombes, 03 86 32 20 79), and we were quickly impressed. Regional cheeses, charcuterie and wine; roaring fire in the fireplace; entertaining conversation with Michel and with the Chef. Then off to bed in comfortable rooms, simply but attractively furnished, to sleep the deep, restful repose of the countryside.

Then we were there, at l'Auberge de l'Atre in les Lavaults (Des Poissons si Grands, http://www.auberge-de-latre.com, Les Lavaults, 89630 Quarré-les-Tombes, 03 86 32 20 79), and we were quickly impressed. Regional cheeses, charcuterie and wine; roaring fire in the fireplace; entertaining conversation with Michel and with the Chef. Then off to bed in comfortable rooms, simply but attractively furnished, to sleep the deep, restful repose of the countryside.

We awoke early Saturday morning to get out onto the river. After a steaming shower and an ample breakfast of fresh baked goods, home made preserves, cheeses and hot chocolate we headed off to the Parc du Morvan. The mist was heavy over the land and clung to trees and stream as we drove deeper into the forest. Michel pulled up alongside a small bridge and we donned waders and vests and made our way down into the knee deep water.

I started just above the bridge and made my way slowly upstream, casting against the current as Michel had directed. Present the fly from the behind the trout, he had said. I could expect the fish to be facing upstream, and I didn’t want him to see the line. Permit the fly to float briefly in the current and then recast. I followed his guidance, working in small arcs, covering each of the slicks and riffles that seemed likely resting places for the wild trout.

Soon I had my first hit. A quick, solid bump and then it was gone. I’d failed to set the hook. A burst of adrenaline, then nothing. I continued to wade and cast.

Soon I had my first hit. A quick, solid bump and then it was gone. I’d failed to set the hook. A burst of adrenaline, then nothing. I continued to wade and cast.

Before long I had another hit. This time my response was quicker, gentler. I set the hook and allowed the small trout to run briefly then began to reel. He thrashed, breaking free of the water then made another run, shorter, less forceful. I landed a beautiful brown speckled trout and looked around to see if Michel or my colleague were around to show off my prize. But they had already made there way upstream, so I removed the barbless hook from the small trout’s mouth and returned him to the current from which I had removed him only moments before. He disappeared in a flash, and I stepped several paces to resume casting.

We spent an overcast morning on this secluded river filled with darting trout. The fishing was challenging but rewarding. Small, savvy trout taken by wit and released with respect. I never saw another angler, and by the time Michel invited us to take a break for lunch, my rhythms had been successfully recalibrated to the soothing river and its rustic environs. The mist had evaporated and the sky was blue as we drove off to Quarré-les-Tombes for lunch.

We enjoyed lunch in this small, rural town followed by folk music and dances, and even met some of the friendly locals. We had the sense that Quarré-les-Tombes is not often frequented by too many tourists despite the mysterious and slightly haunting collection of sarcophagi displayed around the church; this pleased us with Michel’s choice. After eating, it was back into the Morvan to while away the afternoon on another even more idyllic river. I had considerably less luck fishing but enjoyed myself as much as I had during the morning.

We enjoyed lunch in this small, rural town followed by folk music and dances, and even met some of the friendly locals. We had the sense that Quarré-les-Tombes is not often frequented by too many tourists despite the mysterious and slightly haunting collection of sarcophagi displayed around the church; this pleased us with Michel’s choice. After eating, it was back into the Morvan to while away the afternoon on another even more idyllic river. I had considerably less luck fishing but enjoyed myself as much as I had during the morning.

When dusk neared we headed off toward Vauban for dinner and lodging at l'Auberge Ensoleillée (L'Auberge Ensoleillée Hôtel-Restaurant, Maison Blandin, 58230 Dun-les-Places (Nievre), 03 86 84 62 76). This extremely rustic inn had been highly recommended by our guide, and his expertise on the rivers during the day had earned our trust during the evening. We didn’t linger for long in our cramped quarters but headed down to the noisy restaurant, packed with locals. Michel ordered great quantities of all sorts of local delights including mounds of “cuisses de grenouille” (frog’s legs) drenched in garlicky butter and simply cooked “filet de sandre” (trout?), also swimming in butter. Plenty of very rich, delicious comfort food. And friendly service from the inn’s owner who waited on and chatted with us all evening.

After a long, excessive gorging, we retreated upstairs to our respective quarters. Upon entering my musty room, I contemplated a late-night stroll to exorcise some of calories I’d just ingested. I exited my room, walked to the end of the corridor and stepped out onto the second story landing. The night was inky black, humid and cool. The only noises, aside from the clanging of pots and pans being washed up downstairs in the restaurant, were a couple of dogs barking in the distance, and the “peepers and croakers” that I associate with Adirondack summers. The calm was inviting, but the wine and heavy meal were already slowing my metabolism, encouraging me to get some sleep. So I did.

Another deep slumber followed by another hearty country breakfast, this time sitting on an enormous flat stone table/bench in front of the inn. The night’s chill was yielding to the sun’s warmth, and the cocoa and fresh-baked croissants induced the sort of contentment that animals must feel in springtime after a long hibernation. A lethargy, an urge to linger and absorb warmth. To energize by degrees.

Another deep slumber followed by another hearty country breakfast, this time sitting on an enormous flat stone table/bench in front of the inn. The night’s chill was yielding to the sun’s warmth, and the cocoa and fresh-baked croissants induced the sort of contentment that animals must feel in springtime after a long hibernation. A lethargy, an urge to linger and absorb warmth. To energize by degrees.

I had been up for an hour or two, wandering around the town, snapping pictures before anyone was awake. The morning was ripe with color, bright, bold pigments emerging from a misty morning. A wayward rose bursting throw a trimmed evergreen hedge in front of a church. An abandoned tractor planted in front of a storage container. A sky blue barn door. Crisp, primary colors, dancing in a rural composition.

We packed up and headed back onto the river as Sunday church-goers began to traffic the bumpy roads leading into town. Michel brought us to a different stretch of water than we had fished the preceding day, and he lead us off in two different directions, my colleague upstream, and I downstream. He accompanied her, and I set out alone, making my way along the bank toward a bend that he had described for me in great detail. After a while I recognized the lazy current he had predicted and made my way along the inner bank of a bulging meander where I identified the ruins of a stone bridge overgrow with moss. Just downstream lay a picturesque stretch of water, speckled with almost submerged boulders.

We packed up and headed back onto the river as Sunday church-goers began to traffic the bumpy roads leading into town. Michel brought us to a different stretch of water than we had fished the preceding day, and he lead us off in two different directions, my colleague upstream, and I downstream. He accompanied her, and I set out alone, making my way along the bank toward a bend that he had described for me in great detail. After a while I recognized the lazy current he had predicted and made my way along the inner bank of a bulging meander where I identified the ruins of a stone bridge overgrow with moss. Just downstream lay a picturesque stretch of water, speckled with almost submerged boulders.

I waded into the gentle current, fly rod in hand, already mesmerized by the burbling stream whispering seductive tales of the past. I’ve tried to convey the zen-like appeal of fly fishing to the uninitiated and failed. To skeptics and detractors it is simply another type of hunting, predator stalking unsuspecting prey. A barbaric pastime for rather esoteric fly-tying, insect-hatch-monitoring loners. I’ll resist the temptation to refute these misconceptions if for no other reason than to discourage the masses from choking up the pristine rivers and streams of our planet. But suffice to say, it was the serene, meditative state that sometimes comes over me when lost in the solitude, senses awake to the breathing of the world around me, courting the elusive fish lurking in the shadows, it was this rapture that I most remember from my morning on the river.

Casting beneath overhanging branches, I tried to stretch each cast deep into the shade, to present my dry fly as daintily as possible. Matching my wits against the ever-more-acute wits of the fish, I practiced my casts (and in my experience with fly fishing, it is always practicing, always striving for more extension, greater precision, better presentation, striving—but never achieving—perfection). Subtlety, finesse, patience. I love the sound of the heavy line, somewhere between a faint whistle and a distant singing, as it arcs through the air during a false cast, then glides outward toward its target.

Casting beneath overhanging branches, I tried to stretch each cast deep into the shade, to present my dry fly as daintily as possible. Matching my wits against the ever-more-acute wits of the fish, I practiced my casts (and in my experience with fly fishing, it is always practicing, always striving for more extension, greater precision, better presentation, striving—but never achieving—perfection). Subtlety, finesse, patience. I love the sound of the heavy line, somewhere between a faint whistle and a distant singing, as it arcs through the air during a false cast, then glides outward toward its target.

It’s easy to romance an afternoon on the river. And annoying to those who have never tried it, I suppose. So I’ll restrain myself here. In fact, I never did catch anything all morning, nor did I so much as see a trout rise to take a fly from the water’s surface. I suspect there were plenty of fish in there, but they were too wise or too lazy to fall for my efforts. Nevertheless, the hours slipped away in a state so sublime that I wasn’t the least bit disappointed when Michel gathered me up for lunch.

My soggy colleague (she had tumbled into the river, filling her waders with water) returned from the forest where she had changed out of her wet togs, and the three of us sat down at river’s edge for a veritable feast. Michel had prepared a picnic banquet of regional dishes (including a rock hard cheese—the sensational “core” must be whittled out of the ¾” inch thick rind with a knife—from the monastery we would visit after lunch), and we drank local wine, ate heartily and embellished our stories. Always stories on a fishing trip, and despite the obvious appeal of the grossly exaggerated account of my colleague’s plunge, it was Michel who told the best tales, apparently endowed with an endless reserve of fly-fishing anecdotes and historical footnotes.

My soggy colleague (she had tumbled into the river, filling her waders with water) returned from the forest where she had changed out of her wet togs, and the three of us sat down at river’s edge for a veritable feast. Michel had prepared a picnic banquet of regional dishes (including a rock hard cheese—the sensational “core” must be whittled out of the ¾” inch thick rind with a knife—from the monastery we would visit after lunch), and we drank local wine, ate heartily and embellished our stories. Always stories on a fishing trip, and despite the obvious appeal of the grossly exaggerated account of my colleague’s plunge, it was Michel who told the best tales, apparently endowed with an endless reserve of fly-fishing anecdotes and historical footnotes.

Following our sylvan banquet, we spent the afternoon wandering in the forest behind the Monastère de la Pierre qui Vire, a 19th century monastery. This enchanted forest near the Trinquelin River transported us into the magical tales of our childhood. And deep into ourselves. Colossal trees, at least a century, maybe two, older than I, soared upwards and stretched vast canopies across the heavens. Sunlight, filtered through the dense leaves, dappled the mossy, boulder-strewn landscape. If gnomes exist, it is here that they smoke their pipes and race slugs for glory.

We concluded the afternoon with a visit to the Basilique de Vézelay, a Roman basilica dating from the 11th  century which crowns a hilltop village of the same name. Grand Dame. Enduring. Imposing. Provocative. Makes the mind wander. Of course, it'd been wandering all weekend... I made my way around to the backside of the church, compelled by a weakness for flying buttresses. Her best side? I'm always drawn to churches’ posteriors. Less self-conscious. Often more elegant. And always more sensuous. The views out over the agricultural hills and valleys from the rear of the basilica aren’t bad either.

century which crowns a hilltop village of the same name. Grand Dame. Enduring. Imposing. Provocative. Makes the mind wander. Of course, it'd been wandering all weekend... I made my way around to the backside of the church, compelled by a weakness for flying buttresses. Her best side? I'm always drawn to churches’ posteriors. Less self-conscious. Often more elegant. And always more sensuous. The views out over the agricultural hills and valleys from the rear of the basilica aren’t bad either.

Then it was time to head back to Paris. We made our way downhill and out of Vezelay. I noticed a car parked on the side of the road. A small white sedan. It had pulled off the road through a break in the hedge and sat at the corner of a recently harvested wheat field, the cut wheat raked into a corduroy pattern that ran back and forth across the field. As we approached, I saw a folding table covered in a white tablecloth behind the sedan. Two elderly men, dressed in cream-colored suits and straw hats were sitting at the table enjoying a picnic supper. A harvester moved slowly in an adjoining field. A small bird badgered a crow overhead. And these men dined.

Then we were past, zipping along the narrow two lane road that wandered from town to town in the gentle hills, field after field hemmed in between hedgerows. I looked back at Vezelay, and the basilica—looking down upon farmland—was rendered almost quaint amid the undulating fields. It was already late afternoon but it was the beginning of July and the sun was still high, bathing this scene in ochre a shade more dramatic than longing.

But we were on our way back to Paris. Along sinuous country roads until the inevitable auto route and the traffic thronged City of Lights. It seemed premature for nostalgia since the weekend was only then expiring, but the feeling was palpable. Michel Winthrop, our eccentric fly fishing guide, doubling as a charming and knowledgeable cultural docent, had concocted the most magical of weekends for our two day escape from the hurly-burly of Paris.