Jaisalmer

During a recent trip to India, my friend and I traveled by bus from Bikaner to Jaisalmer. We had been in Bikaner for only a few hours before voicing our reservations about getting our feet trampled by rats. It didn’t matter that they were holy rats from the Karni Mata Temple in Deshnok, just 30km away. They were still rats.

The bus to Jaisalmer was seven-and-a-half hours, overnight. The rhythmic passage to the desert city took us through the long veins of India in pitch darkness. Throughout the night, the bumps on the roads rattled everything and everyone on the bus. Occasionally, the horn was accompanied by sudden turns that stirred us.

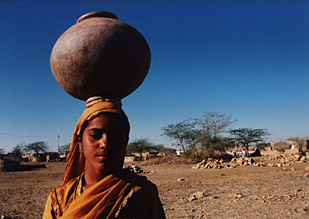

In the morning, the Jaisalmer sun warmed our faces. The streets were sprinkled with sand that had blown in from the desert. We took a rickshaw straight to the Amar Sagar Gate. Standing in the first square, we were dumbstruck by the Golden Fort so close to the deep blue sky. At the top of the Fort, another gate enticed us to go further. The second square was smaller and surrounded by activity. There were restaurants on one side and vendors on another displaying colorful fabric dotted with the mirror work for which Jaisalmer is widely known. My eyes followed the flashes of light flying off the little mirrors. Someone was playing the ever-cheerful Bollywood music nearby to accompany my dancing eyes. Men in colorful turbans sat chatting and enjoying the day.

Walking past the havelis, each one different from the last, we were told that the sandstone the Fort was made from deflects most of the sunlight during the day. This prevents the strong rays from going through, allowing the inside to remain cool. At night, when temperatures drop drastically, the stored heat warms up the havelis. Each one has a courtyard where light is evenly distributed inside. The many intricately carved holes on the stone jalis provide privacy and cross ventilation. Many havelis housed gift shops on the first floor. Stacks of fabric in the brightest colors decorated the walls inside, so many brilliant colors – none clashing, all complementing one another. Other shops offered postcards and toiletry in one corner and Internet service in another.

We had our first meal at the 8th of July Restaurant, run by Rama and Jags Bhatia. Rama was, from the start, a perfect mom. Shortly after we introduced ourselves, she asked if we had “runny tummy,” “tender tummy,” or “stubborn tummy.” I confessed I had the last. She snatched the menu from my hands and told me she had my order already. As she returned with wonderful food remedies, her husband, Jags, spoke to us in enthusiastic bursts. Not particularly interested in making small talk, he got straight to the point about the camel trek we had asked about. Not particularly pushy, he wished us luck and disappeared as abruptly as he had appeared.

Snaking toward the quieter northwestern side of the Fort, cows replaced people on the narrow streets. A pregnant cow stood calmly outside the Hare Krishna temple counting time as the temple bell tolled. Further in, its cousin, measuring the width of the street stood unmoving, aware of its authority. Someone came by, clucking his tongue for us, a signal for the cow to plant its hooves elsewhere.

Arriving at Hotel Simla, we were greeted by a smiling face belonging to Johnny, the cook. We staggered up large sandstone steps to see our room. The bed rested on a wooden platform high above the floor. Two hand-carved sandstone pillars supported the structure. Cushions in bright red and orange filled the corners, and sheer firebrick taffeta drapes softened the light from the courtyard giving our faces a crimson glow.

After unpacking, we ascended to the rooftop. On one side was an open area with tables and wide wicker chairs facing the desert. “Pakistan is coming!” the Indians joked. The sun had started to caste its eye downward. We watched as the fiery reds and yellows lingered in the sky for one last breath. The guest house manager – who came to be known as “Parrot” – waved at the sky, squawking repeatedly, “Goodbye Sun! How are you? Konijiwa! Sayonara!” The guests, too calm to be annoyed, continued gazing at the sky.

That evening, we walked down to the restaurant, Trio, where folk musicians performed each night. The Indian and continental menu was pricey but worth ordering from. On our way out, a woman shouted my friend’s name. I quickly descended the stairs, permitting privacy in case he needed to resolve some unsettled affair… Here, of all places!

Moments later, he caught up with me to tell me it was Elle, someone he knew from Taipei, where we all lived.

She joined us for beans and cheese on toast the next morning on the rooftop of Simla and booked herself a room before she had finished chewing. We ordered honey lemon ginger tea one after another while laughing at the coincidence of our encounter. Looking down from the Fort, we could see the class struggle between animals at the local market. Pigs snorted at dogs for snatching their scraps of food away while crows flapped their wings at goats in anger. And the whole while, chickens stayed under the cows safely pecking away at anything leftover from the battle of their animal kingdom.

| It didn’t take long before the guests at Simla made eye contact with one another. By the end of dinner on the second evening, there was busy chatter and laughter from all of us. Parrot had lit candles at each table and invited a traditional Rajasthani musician to play for us. We were amongst us Indian, Kenyan, Australian, Belgian, Canadian, Argentine, English, Mexican, Taiwanese, American, Japanese and Nepalese. Sensing all the excitement, a Frenchman on the neighboring rooftop leaned over and asked if anyone knew the English for dans la réalité. The Canadian shouted back, “In real life!” |

| By the time we left, the pregnant cow had given birth to her calf and we had made some of the best friends we’ll ever have. And, indeed, it was all very real. |