View from the Sun

I’m not usually the type who likes weddings. My own or others. I’m a funeral kind of person. I find people much more honest in grief than in the joy so often displayed at matrimonial ceremonies.

That being said, there was one wedding I didn’t want to miss: the marriage between the sun and the moon, a solar eclipse, August 11, 1999. As I’d been living in England for the summer, the natural place to witness this event was the southwest coast, Cornwall country. Two and one-half minutes of totality were promised—a darkened sky in the middle of the morning. Though that might not sound like such a big deal in usually overcast Britain, it would in fact be be very special. Birds, momentarily confused, would stop singing as if night had fallen. And if the astrologers were correct, a grand cross configuration of outer planets would usher in a slew of strange pre-millennial energies. Plus, the “powers that be” were warning people that Southern England would turn into a huge mess with enormous crowds, lack of food and water, and anarchist riots. That was my idea of an experience.

Armed with a second-hand tent, air mattress, special viewing glasses, and the optimist’s mandatory bottle of sun block, we made our encampment near St. Just. Originally named after a Cornish giant with a seven league boot size named Uist, the Church threw in the saint to pacify themselves and Emperor Justinian while at the same time, attempting to accommodate the old religion. Sainted or not, it rained horribly the first night. My partner, Andy, and I decided that an inexpensive bed and breakfast was in order. After all, this would be the last eclipse of the century, and rheumatic attacks were not going to spoil it. Not surprisingly with all the rain, we found a place called Noah’s Ark.

Armed with a second-hand tent, air mattress, special viewing glasses, and the optimist’s mandatory bottle of sun block, we made our encampment near St. Just. Originally named after a Cornish giant with a seven league boot size named Uist, the Church threw in the saint to pacify themselves and Emperor Justinian while at the same time, attempting to accommodate the old religion. Sainted or not, it rained horribly the first night. My partner, Andy, and I decided that an inexpensive bed and breakfast was in order. After all, this would be the last eclipse of the century, and rheumatic attacks were not going to spoil it. Not surprisingly with all the rain, we found a place called Noah’s Ark.

“A total eclipse of the Sun is one of the most awesome sights in nature,” said the British Museum lecturer. We had been told that ancient people regarded the eclipses with fear and even after Ptolemy showed their true cause, the eclipses continued to inspire terror. The ancients believed it was the devil’s handiwork. Apparently, on arriving in the New World, humanitarian explorer Christopher Columbus tricked the natives with his deep understanding of the science and pulled off a dramatic move with the aid of the celestial bodies. As the skies darkened and then relit, the poor souls believed that Columbus was the true god. We wondered how the hordes of expected anarchists could possibly upstage a piece of theater as spectacular as this natural event. It didn’t take long to find out.

Penzance, a sea town known for its Pirates and a disturbing sounding main road called Market Jew Street, was bustling. As for the street name, all I could find out was that Thursday was the original marketing day in this region, and the Cornish word for Thursday sounds like Jew… So, apparently no harm was meant. Half believing this, I stopped at the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) stall on the street to peruse developments in the peace movement. Helming the attraction was a burly-looking character, half man, half goat, hiding what I would later find out to be silver dreads under a macramé cap.

was bustling. As for the street name, all I could find out was that Thursday was the original marketing day in this region, and the Cornish word for Thursday sounds like Jew… So, apparently no harm was meant. Half believing this, I stopped at the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) stall on the street to peruse developments in the peace movement. Helming the attraction was a burly-looking character, half man, half goat, hiding what I would later find out to be silver dreads under a macramé cap.

Peter M. Le Mare was the CND delegate from southwest England and, out of sheer stubbornness and a belief that the planet should continue spinning, he had been passing out leaflets twice a week for twelve years. He also claimed to be the only anarchist living in these parts and was incensed by rumors that were being spread from London about potential rioting. We talked about the “issues” for a few moments while Andy, playing the guitar for extra spending money, sang “Give Peace A Chance”. It was a definite IMAX moment.

Peter assured me that no aspersions were being cast on Jews by the street name Market Jew Street. His theory was that it received its nomenclature from the traders who sailed to Cornwall in the early days, Phoenicians probably, maybe Hebrews. I had never thought of the Jewish people as having been known for their nautical skills, but said nothing. Peter was absolutely strident in his political correctness and couldn’t imagine that a cultural slur was intended.

Part of my excitement in being in Cornwall was the opportunity to see the sacred stone sites. I had been impressed with Stonehenge and wanted to visit some of the holy wells where King Arthur had sipped. If Merlin were hanging out, even better. It wasn’t until a week later that I discovered that sixties’ author and fun man Ken Kesey was on the same search, though I personally never ran into his magic bus. People from all over were looking for a sense of romance, and Peter offered to help us find it if we helped him hand out pamphlets in the beautiful tourist town of St. Ives.

His brochure was clever. It lured in the passers-by with a cover page, “which eclipse—for your safety”. Inside it was filled with facts about nuclear energy eclipsing our lifestyle. People politely took the paper, having no idea it wasn’t about eye protection. Luckily most of them did not disrupt their vacation by actually reading the dire news. The threat of a nuclear holocaust destroying the earth would certainly have eclipsed any other event of the week. Peter was actually creating a surreal art piece, but only Andy and I noticed.

Besides nuclear proliferation, Peter was upset that the media had discouraged so many people from attending the event with warnings of hot water and food shortages. Travelers or gypsy-style folk were particularly being discriminated against, with harsh warnings about their rude behavior and personal sloppiness. Farmers had put out huge boulders in their fields to discourage treks across them to the sacred sites. At each new boulder, Peter would raise his fist in the air and yell the name of some government person who was contributing to the “de-spiritualization of Cornwall”.

Besides nuclear proliferation, Peter was upset that the media had discouraged so many people from attending the event with warnings of hot water and food shortages. Travelers or gypsy-style folk were particularly being discriminated against, with harsh warnings about their rude behavior and personal sloppiness. Farmers had put out huge boulders in their fields to discourage treks across them to the sacred sites. At each new boulder, Peter would raise his fist in the air and yell the name of some government person who was contributing to the “de-spiritualization of Cornwall”.

For his part, travelers were just people who decided to live outside the system. Peter picked them and other hitchhikers up at any opportunity, even when they didn’t really want a ride. No matter how filled up his small car became, he would invariably try and stuff another body into the boot. As expected, he constantly apologized for owning a car and using petrol, but lived with his old dad who “might need a lift at some point to the hospital”.

As the days grew closer to the eclipse, there were two burning thoughts in people’s minds. Would the rain clouds ruin the sighting and would those promised hordes come after all? As Peter was busy, we hitchhiked one morning into Marazion, a tiny village well known as the center for Phoenician Jewish sailors, with a retired captain of the CID (Central Intelligence Division). Naturally, I made no mention of knowing the infamous Peter the Anarchist to “Dick Ford” as the captain liked to call himself. “Dick” had been imported to Cornwall from London’s Scotland Yard, given a huge house and a bunch of pensions. He was living the good life and was writing a novel about his work. One of the characters in his book was an ex-body smuggler, now a friend. This guy had smuggled immigrants into Marazion by boat through France for a fixed price. In the middle of the ocean, he would up the ante and, if the immigrants didn’t pay, toss them into the sea. When I innocently asked if Captain Ford liked Cornwall, he said “it’s great here, except for the Cornish. They create so many problems. They ruin the place, they’re like your Indians.” Luckily it was only a short car ride.

Back in Penzance where we were buying sample bottles of locally produced mead, the cashier was unwittingly contributing to a game of Chinese whispers. She was telling a customer how all the anarchists had arrived in St. Ives and “were breaking up a Tesco’s.” Tesco, the English version of an upscale A&P, is almost sanctified; you don’t mess with it. The sales clerk at that Tesco’s had been so frightened, “she took to bed.” Andy and I found the story odd. We had been in St. Ives on the day in question with Peter and had seen or heard nothing like an anarchist riot. But these women were convinced it had happened and were waiting with anxiety for the anarchist showdown promised for Penzance. Perhaps not surprisingly, the very next day, a man in St. Ives told me there had been massive riot in Penzance the day before, the same quiet day I had been buying mead. The closest thing that I had seen to rioting was the final call for drinks at the Bull and Cock pub as the clock neared eleven.

Back in Penzance where we were buying sample bottles of locally produced mead, the cashier was unwittingly contributing to a game of Chinese whispers. She was telling a customer how all the anarchists had arrived in St. Ives and “were breaking up a Tesco’s.” Tesco, the English version of an upscale A&P, is almost sanctified; you don’t mess with it. The sales clerk at that Tesco’s had been so frightened, “she took to bed.” Andy and I found the story odd. We had been in St. Ives on the day in question with Peter and had seen or heard nothing like an anarchist riot. But these women were convinced it had happened and were waiting with anxiety for the anarchist showdown promised for Penzance. Perhaps not surprisingly, the very next day, a man in St. Ives told me there had been massive riot in Penzance the day before, the same quiet day I had been buying mead. The closest thing that I had seen to rioting was the final call for drinks at the Bull and Cock pub as the clock neared eleven.

Who was starting these stories and why? It certainly wasn’t helping tourism, having already lost incredible amounts of revenue due to the government and media scare. Whole fields prepared for campers lay empty, B&B’s remained vacant. For my part, I was glad the place wasn’t overrun. That meant there were plenty of spare Cornish pasties to devour. Pasties are basically like a meat or vegetable pie, and I had enjoyed complaining about their starchy heaviness until I found out about their original use.  Coal miner’s wives would prepare the midday meal for their men in one dish, the pastie. The meat would go in, followed by the potato, and next the vegetable. This was designed to give the miner’s a feeling of eating a complete dinner on a plate. Some cooks would actually put fruit in at the very bottom of the pastie, so they could eat their dessert after the entrée. And the crust was three inches thick to keep the diner from poisoning himself by accidentally licking his fingers, long since impregnated with arsenic from working in the mines.

Coal miner’s wives would prepare the midday meal for their men in one dish, the pastie. The meat would go in, followed by the potato, and next the vegetable. This was designed to give the miner’s a feeling of eating a complete dinner on a plate. Some cooks would actually put fruit in at the very bottom of the pastie, so they could eat their dessert after the entrée. And the crust was three inches thick to keep the diner from poisoning himself by accidentally licking his fingers, long since impregnated with arsenic from working in the mines.

Poor blokes, as if poison weren’t enough of a worry, they also had to save and throw the pastie crusts to the little faeries, called “knockers”, who lived in the bottom of the coal mines. The knockers’ job was to protect the men from danger if given sufficient crust. And all I had to do was try and digest the things.

It was the day before the Big One. Peter had taken us to a lovely stone circle where I performed a minor healing ritual and allowed the ancient pagan and Hebrew energies to permeate my urban armor. Invited back to Peter’s for a cheesy vegetable dish, we met his nearly blind eighty-plus year old father who looked suspiciously like George Bernard Shaw. His dad was one of the first Quaker/pacifist/socialist/communists and insisted the families’ real claim to fame was never once standing up for the playing of “God Save The Queen”. Also there was Brit anti-war heroine Andrea Needham, one of four women who had hammered a Hawk aircraft bound for bombing in Indonesia. She had won in British court by proving that her action prevented a greater crime from occurring to the people of East Timor. We toasted each other with a great wine and wished for a sunny wedding the next day.

On top of Trencom, an ancient hill, we stood with a few hundred others on that special Wednesday, waiting for the bride to meet her groom. One family had come with a plant that goes to sleep when it gets dark as an experiment to see if it would actually change position when the moon’s shadow made her historic move. It was so cold, I personally thought the plant would have been happier sleeping at home in a window box. It was pouring pellets, extremely cloudy and bitter. As the hour approached, a mustached man from Manchester held up a cover of Time Magazine with a picture of the eclipse, and announced “this is what we’re supposed to be seeing now.”

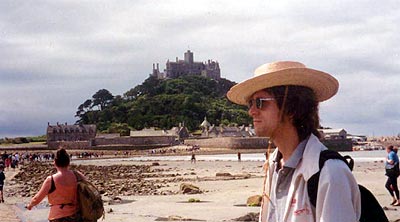

experiment to see if it would actually change position when the moon’s shadow made her historic move. It was so cold, I personally thought the plant would have been happier sleeping at home in a window box. It was pouring pellets, extremely cloudy and bitter. As the hour approached, a mustached man from Manchester held up a cover of Time Magazine with a picture of the eclipse, and announced “this is what we’re supposed to be seeing now.”Suddenly, from the western side of the hill, I heard an American accent. Melody, from Los Angeles, had come with a group of Jungians who were exploring the meaning behind the eclipse and the consciousness shift expected with the millennium. They were serious researchers of this realm, but didn’t have umbrellas. We brought Melody in underneath our Tote, and the three of us started to chant, “Here comes the Sun.” But the sun refused to come. Instead the sky turned to black and all across the horizon little pops of light were glittering. Cameras were being flashed from every point. It was truly magical realizing that others like us were doing the exact same thing at many different places, freezing and taking pictures. To share a moment with so many, at an event that wasn’t connected to a religion, a political machine or a rock star, was profound. When the “lights” came back on and the castle of St. Michael’s Mount could be spotted in the background, a huge cheer went up. It felt like a sense of renewal, only temporarily spoiled by the man who announced to his wife and their crowd, “Next year we’ll watch this in Africa, the weather’s better. Only problem will be the Africans”. Strains of Captain Ford from Marazion. As soon as the man said it, he wished he hadn’t as the shocked sounds of disapproval flowed through the morning air as passionately as champagne flowed into the paper cups.

A final drink with Peter, the world’s friendliest anarchist and his Thai wife, Anna. Anna told us that her actor father had taken her into a hotel room when she was only twelve to introduce her to a famous American film star. Marilyn Monroe greeted them stark naked, presumably because of the unrelenting Thai heat, and remained that way throughout their entire visit. Even as a child, Anna remembered that Marilyn had a beautiful body. So we shook the hand that shook the hand. The separations became narrower and narrower.

Still not wholly satisfied with Peter’s theories on the origin of the name Market Jew Street, I turned to A. N. Wilson’s book, Jesus, in a St. Ives’ book shop and read that a wealthy Jew named Joseph of Arimathea had brought his ships to Cornwall for the tin business. That made sense. Cornwall I had learned had been the greatest source of tin and copper in the western world. There were many vacated tin mines. But here’s where it got fuzzy. Apparently, he brought the Christ child with him on one occasion and they landed on St. Michael’s Mount, the first place we spotted after the eclipse. Plus Joseph was also the bearer of the famous thorn tree in Glastonbury, whose very thorns were used to decorate Jesus’ head on his final day. I may be thick, but I still don’t understand how the thorns got back to the Holy Land in time for the crucifixion and am even more surprised that Jesus’ mother let him travel with tin merchants before his Bar Mitzvah. So only some of the mysticism of southwest England got partially explained, including the question of Zion in Marazion? Next I was expecting to hear that King Arthur was from the tribe of Levites and that the round table was actually in the shape of the Star of David.

Putting all such thoughts aside, I ordered a round of drinks at the local St. Just watering hole. Andy nudged my arm to inform me that sitting on the next stool was a world class violinist. I turned to the hairy guy on my left, picked up his paw and asked if the hand belonged to a first class fiddler. It did indeed; he was Nigel Kennedy, freshly returned from performing at the Eclipse Lizard Festival. He was feeling great and thought that the energy was fantastic. And he hadn’t seen a riot anywhere. We joined him for a music jam in the garden with Peter shaking the plastic percussion egg. Nigel said that he had a clear sense that we were all at the precipice of a new beginning, a new way of being, and a new way of responding to each other. Why not, we’ve tried the other ways. As the sun set, I sipped the last of my bitter and was truly grateful that this was one wedding invitation I hadn’t turned down.