Haida Tales

On the southern tip of a windswept archipelago sixty miles off the coast of mainland British Columbia, lie the remains of a great civilization.

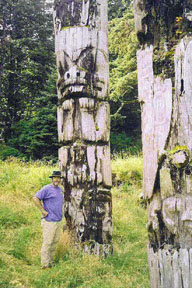

Tucked into a sheltered cove on the East Side of Anthony Island, the once thriving village of Ninstints (or Skuun Gwaii, or Sung Gwaii; there are many local spellings) is guarded by the last standing giants of the Haida Nation. Twenty-six totem poles carved by Haida masters stand in silent watch over the land.

The Haida people are native to these islands, and have an ancient history rich in both art and warfare. Their oral history can be traced back for 7000 years. The early people called their land "Xhaaidlagha Gwaayaai," or "Islands at the Boundary of the World." The name has since been shortened to Haida Gwaii, or "Land of the Haida." Most of the world calls this archipelago the Queen Charlotte Islands. They number more than 1800 in all, and are part of British Columbia, Canada.

been shortened to Haida Gwaii, or "Land of the Haida." Most of the world calls this archipelago the Queen Charlotte Islands. They number more than 1800 in all, and are part of British Columbia, Canada.

The earliest recorded information on these islands came from Spanish explorer, Juan Perez who discovered them in 1774. A decade later, Russian fur traders began to frequent them and for the next century they were the only non-native visitors. The islands got their current name from the flagship of Lord Howe, the H.M.S. Queen Charlotte, who was the wife of King George III of England.

As a seafaring people, the Haida carved enormous war canoes from a single cedar tree. The canoes were large enough to carry dozens of warriors over sixty miles of open ocean to raid villages and take slaves on the mainland. They were fierce warriors and have often been called the "Vikings of the north." The Haida also carved the first totem poles to honor their accomplishments and leaders.

Before white contact, the Haida people had already raised carving to a high art form. The introduction of metal from Russian fur traders allowed them to fashion new and more efficient tools, increasing their skills tenfold. The Haida carved wood like most of us breathe, and they did it on a monumental scale. House columns, commemorative totems, burial boxes, and even ornamental bowls were all of the highest quality.

A Haida chief named Tahayren, who later took the British name, Charles Edenshaw, is generally acknowledged as one of the finest carvers ever.

Upon his death, his carving tools were passed on to his nephew, Charles Gladston, who is the grandfather of Bill Reid. Reid, whose Haida name was Iljuwas Yalth Sgwansang, died only a few years ago. During his life, he continued the great tradition of carving and started a resurgence among young Haida in the art form. Today the work of Reid and Edenshaw resides in the world's finest museums as examples of the epitome of Haida carving. Reid is buried at the village site at Tanu and his grave is a revered place for the Haida people.

On our way south, we stop at Tanu and leave a few seashells on the headstone of Bill Reid as a small thank you for what he has left us, and take a few minutes to view the totems remaining at this site. There is an impressive Sea Bear and what I have been told is a calendar totem, but this is not our final goal. These poles sit back in the woods and do not have the dramatic impact of the carvings at Ninstints.

At the apex of Haida culture, close to 14,000 people occupied these islands with almost 300 living in Ninstints. The village name is a western mispronunciation of Nan Sdins, who was chief at the time of white contact. Around 1860, small pox was brought to the islands by white fur traders and soon only about 30 people were left alive at Ninstints. By 1911, the total native population of the islands stood at 589. The village was totally abandoned around 1880, but the exact date is lost to history.

I have sailed from the capitol city of Skidegate to visit the site at Ninstints before weather and time claim the remaining poles forever. We fight our way south on an old fishing trawler in storms powerful enough to sink an Alaskan Ferry and two commercial fishing boats. After a night of dragging our anchor around in high winds, we land on the backside of Anthony Island in our Zodiac. Going ashore is treacherous, and the heavy seas that are normal here make me appreciate the ocean-going abilities of the Haida. To our west, there is only open water until you hit Japan. We must slog through a mile of knee deep mud that tries to suck our boots off, before reaching the village in its protected cove. The first site is breathtaking.

The poles are bleached almost white from the sun and their storied faces are mostly worn smooth by the relentless Pacific winds. Yet there is still much to be seen. Several of them are funeral poles that once held wooden boxes with the remains of Haida nobles. The early Haida buried their chiefs by compacting their bodies into a tiny wooden box that was placed at the top of a burial totem in front of the chief's lodge. The carvings on each totem tell the story of significant events in the man's life; there is nothing random in their design. Each rendered image, whether real or imagined, has a specific meaning: a wedding, a death, or a great battle, for example. The meanings of many carvings are known only to the people that are now long gone.

At the height of Haida culture, their villages, which always sat on the shoreline, were adorned with dozens of totems and large carved support poles for their longhouses Their canoes and paddles were carved and decorated, and they made functional clothing from the bark of cedar trees. These people spent their lives in and of nature, constantly surrounded by their art.

The various animal and otherworldly creatures that stare at us from these poles have been weathered to the point of making specific identification very difficult, but the erosion in no way diminishes their individual power. I can decipher a beaver; thunderbird and sea bear from their resemblance to other works I have seen, but that is all. To walk among the poles is to feel the presence of the people who carved and lived beside them. While they stand, this village still lives. They all face south to the sheltered cove that is the village entry. The view from a canoe on the water a century ago must have been impressive.

I am dwarfed by their sheer size and feel insignificant in their presence, for most are well over ten feet tall. I am in the presence of ancient giants.

Here in the silence of this burial ground one can feel the overwhelming history of these islands and their people. I have a sense that the poles will begin to speak at any moment or perhaps dance to tell us their secrets.

Many native people believe that a totem should stand in nature and slowly deteriorate until it returns to the land from whence it came. Others have tried to save these poles for posterity, and in 1995 a large-scale restoration project was undertaken with the consent of local Haida elders to prop up some of the poles in danger of falling. Some have been removed to museums. Originally there were 35 totems here, and now there are only 26.

The old Haida villages were always guarded from attack by a watchman. This was an honored position within the tribe, and the watchmen were distinguished by wearing a conical hat made from cedar bark. Many of their totems, including contemporary ones, are topped by carved watchmen who stand guard. Today, the Haida people have reinstated this program and each native site has a watchman on duty. Visitors must gain permission in advance before landing on any of these beaches.

In 1981 Ninstints was declared a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), guaranteeing its preservation for the immediate future. Unless these poles are removed, they will eventually be reclaimed by time and weather. For now, they are a magnificent testament to a vanishing culture